All I did was walk into the kitchen and pick up a cloth. But the sudden waft of bleach flung me far, far back into some childhood memory. I switched to a traumatised part of myself. I had been ‘triggered’.

Physically, I revved up into the panic and distress of the fight/flight response, everything in me taut and straining to protect me from some unseen danger. My heart lurched inside me. It’s just bleach, I tried saying to myself, desperately. Just bleach. And I strained with everything I had to feel real again, to stop this mad descent into terror and shame and darkest, deepest dread.

I wonder sometimes how any of us manage to work, or parent, or socialise, or go shopping, or even sleep, when this is happening all the time. And for me there was a period of 3 or 4 years when it was constant. I made several suicide attempts during that period of my life, because it was so bewildering, so overwhelming, so exhausting. I never want to go back to that kind of misery again. Being on the other side of it now, I feel strongly that we need a solution to triggers – it’s not enough just to sympathise.

The shame of triggers

I struggled too with the shame of being triggered. I didn’t want to be like this. I hated people noticing. I wanted to shout and scream that I hadn’t caused the abuse, so it was unfair to have to deal with the consequences. I railed against the unfairness, wanting everyone to listen. Why should I have to do the heavy lifting of dealing with triggers? I didn’t cause them! But eventually I realised that no amount of anger or resentment would change the fact that I was being triggered, and that no one else was going to do anything about it – that no one else could do anything about it. Only me. So I had to learn how to deal with triggers better.

The trigger warning

But we live now in the world of the trigger warning. Every day on social media, I see posts trailered by asterisks, blank lines, those ominous words ‘trigger warning …’ Each week we receive emails from people detailing words, situations, people or images that ‘triggered’ them. One person is triggered when trapped in a lift with a stranger; another by the picture of a tree in their therapist’s office. For some it’s words like ‘abuse’ or ‘sex’; for others simply the letter ‘x’.

But what does it mean to be ‘triggered’? The word means different things to different people, and therein lies our confusion as to what constitutes a trigger, and when a trigger warning may need to apply. With a fear of causing upset we err on the side of labelling everything a trigger. But by doing so, we lose a sense of scale – the word ‘abuse’ as a trigger is conflated with the actual experience of being assaulted. And we lack the confidence to know how to deal with these reactions. Triggers evoke your powerlessness at the moment of trauma, and they whisper to you that you are still powerless now. It makes recovery from trauma seem impossible.

Many people, believing that triggers are uncontrollable, immutable and inevitable, assume that we must avoid them, and ask others to avoid them too: hence the rise of the trigger warning. Certainly when we’re assaulted day and night by them, logic suggests that our reactions cannot be controlled. After all, none of us choose to be triggered – so how we can choose not to be triggered?

The cost of avoidance

But there’s a cost to coping with triggers through avoidance alone. Our world narrows to the point of imprisonment: if open spaces are triggering, we can’t go outside; if small rooms are triggering, we can’t stay inside; if things in our mouth are triggering, we can’t eat; if our bed is triggering, we can’t sleep. Hence why life with unresolved trauma is so debilitating, when there are so many situations to avoid. Avoidance is a smart survival strategy, but it comes at a price.

So what if there’s a way to neutralise triggers, rather than just avoid them? Can you even imagine that?! What if we didn’t have to avoid life, but could enjoy it? Wouldn’t that be life-changing?

And it is, and I know this – again from personal experience. It is possible to live a life where triggers no longer hold sway, where most of the time I can stay in the ‘green zone’, in my ‘window of tolerance’. And what a transformation it has been – it makes life liveable again.

Why are we triggered?

So in order to learn how to neutralise triggers, we need to go back to basics and figure out what triggers are and why they exist. Let’s stop and consider: how do we manage to stay alive? What stops us from walking off cliffs, playing with fire, jumping into traffic, sitting down on a dual carriageway?

Fear.

Fear is an emotion, a feeling we have, which helps us avoid danger. It can be based on reality – it’s right to fear a man with a gun – or it can be a natural fear ramped up to an extreme: we can’t reconcile hurtling through the air in a tin can at 30,000 feet, so we develop a fear of flying. To ensure our safety, fear exists in anticipation, before the event, so with a fear of flying we might start reacting physically even just thinking about planes.

That feeling of fear is an awful one. It’s very visceral – you feel it in your guts. It starts with an uneasy, anxious sense of dread. Your tummy is queasy and your muscles are taut. As it increases, you might feel shaky; your throat might go dry; your heart begins to thud in your chest; you might feel like you can’t breathe, or you start hyperventilating. It’s a really aversive experience. Everything in you is screaming to run away, to make it stop. And of course it does – how would we know to avoid dangerous situations if we didn’t have so strong a physical reaction? Our fear response is intended to keep us safe, to ensure we survive.

When we encounter a dangerous situation – a near miss on the motorway, a gunman, a fall near a cliff – our body reacts instantly to ensure we do something to deal with this danger. We swerve; we duck; we grab onto something. So our internal alarm sets off a chain reaction in our body of physical responses – mainly adrenaline, causing our breathing and heartrate to increase so that energy is available for us to deal with the threat. The feeling we feel is of fear, and panic.

When we suffer some harm from this threat – when our efforts to defend ourselves aren’t sufficiently effective – then our body does the next best thing it can to survive. It goes into a submissive freeze response. It might curl into a ball to shield itself and to hide from view; it might play dead; it won’t resist. It’s a clever survival strategy that might be the only thing that actually saves our life, but it leaves us with an enduring sense of powerlessness and helplessness, that there was nothing we could do. The survival brain, seeing what has happened, marks this event as ‘extremely aversive’ and plans from that moment on to avoid it happening ever again. If you can’t beat it, avoid it. Forever. It becomes both a physical and psychological imperative.

So to avoid it, we need some clues that it might be happening again. Was it raining when it was happening? Was it a man? Was there a smell of alcohol? Was he wearing a red jumper? The basic, survival brain adds all of these elements to a ‘threat list’. So the next time it’s raining, or there’s a smell of alcohol, the alarm goes off again: look out, threat coming! It’s as aversive as the original event. The brain doesn’t check that it’s right. It prefers to have the earliest possible warning, even at the risk of a false alarm. A delay could mean death, rather than life. React first, ask questions later …

That’s a trigger in action. A trigger is a reminder, conscious or unconscious, of a traumatic event. It’s something that sets off the alarm system in the body and brain to prepare us for a threat. The problem with triggers is that they elicit such a powerful response in the body, but they’re not always accurate. The amygdala, the brain’s smoke alarm, is a basic piece of kit and it generalises and jumps to conclusions – better safe than sorry. So after trauma it goes off at the slightest hint of smoke, telling us that burnt toast is as dangerous as the house on fire.

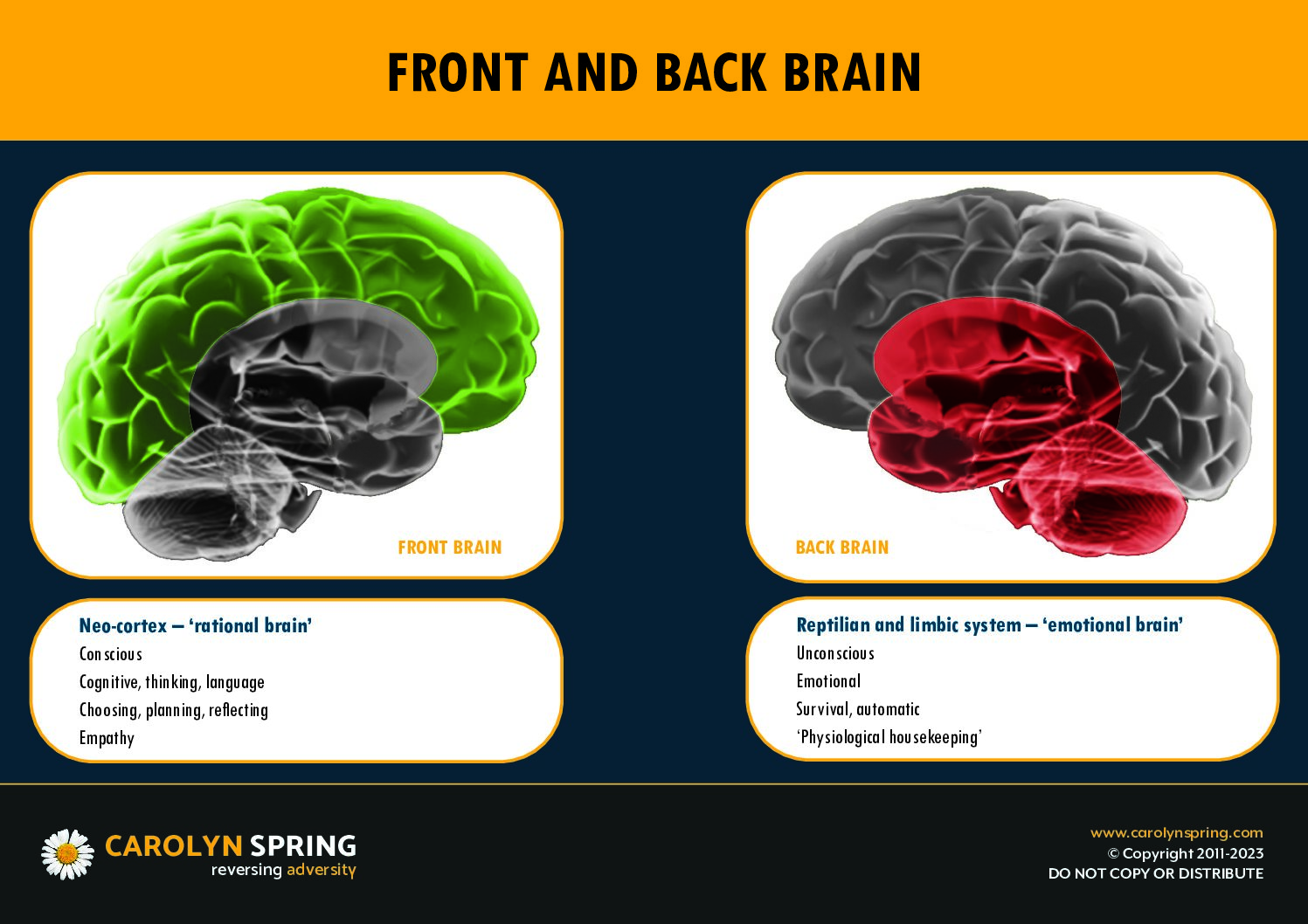

So a trigger in the strictest sense is something which activates the smoke alarm. It all happens in the blink of an eye, within 7 milliseconds. The survival-based back brain, which houses the smoke alarm, makes the decision before our conscious, thinking front brain gets to take a look. It all happens unconsciously, before we’ve had a chance to choose. In that sense, we are not choosing to react to a trigger. It’s all beyond our conscious processing.

So if a trigger is something which activates the body’s autonomic nervous system (with fight, flight or freeze – into the amber or red zones), then do we use the word accurately? Or do we use the word ‘trigger’ to mean other things as well? Do we use it to mean ‘anything which causes an unpleasant feeling’?

A personal story

I used to find dogs a huge trigger. And in the midst of my breakdown, I sat in a seminar at a survivors’ event, and in came another delegate with a guide dog. She sat on the front row, diagonally opposite me, unintentionally blocking my exit. I was triggered. I felt irrationally upset, like I wanted to burst into tears, but I didn’t even know what at. I had a strong flight reaction – I just needed to get out of there. My heart was pounding and I could hardly breathe. But I couldn’t move – at least I felt I couldn’t, because the dog was in the way. In reality, if my front brain had been working, I could have figured out a route around the back of the room, or I could even have asked the owner if she could move to let me past. I could have asked someone else to ask the owner to move. In reality, there were a number of options open to me, but I couldn’t see them in my terror and freeze.

If I’d had some scripts or mantras, I could have grounded myself. I could have said to myself, ‘Okay, I’m being triggered by the presence of this dog. It’s bringing up feelings, sensations and memories from the there-and-then. But what’s going on in the here-and-now? Am I in danger from this dog? Or is it in fact just sitting there, completely uninterested in me? What is the actual risk, right here and right now? Can I just notice that this is ‘a’ dog, but it is not ‘the’ dog?’

The distinction between ‘a’ dog and ‘the’ dog was a breakthrough for me. As I walked down the street and was approached by walkers and their dogs, I began to say, over and over to myself, ‘It’s okay. This is ‘a’ dog, but it’s not ‘the’ dog’.’ I forced my brain to make the distinction between the actual, specific trigger at the time of the trauma, and the way I have generalised out from that. I got my front brain to start ‘just noticing’ and to play spot the difference: ‘This is ‘a’ dog, but it’s not ‘the’ dog. ‘The dog’ was a Border Collie. This dog is a Staffie. ‘The dog’ was alive during the 1980s and must have been dead for over twenty years. ‘This dog’ is safe.’

Three types of trigger

Instead, I think there are three things that we tend to lump together and call a ‘trigger’, in decreasing order of severity: true triggers, distressing reminders and uncomfortable associations.

True triggers

True triggers occur when our smoke alarm is activated by something in our environment – it’s usually a felt sense, a real re-experience. Rather than just a picture of a tree, it’s finding yourself under a tree, with the smell of undergrowth, the dappled sunlight, the crunch of twigs underfoot. The information comes in through the senses and sets off the smoke alarm to full alert. The front brain goes offline; the back brain comes online; and it is very difficult to manage our response as we have such reduced mental functioning. Our response occurs within 7 milliseconds, before conscious thought has had a chance to be engaged – it is, as Judith Lewis Herman described it, ‘wordless terror’. It is principally a body-based response, directed almost entirely by the back brain and is mediated solely by the amygdala. The key to dealing with them is the magic phrase ‘just notice’, engaging the front middle brain (the medial prefrontal cortex), although to start with we might only begin to address them afterwards. But, as the saying goes, better late than never!

Distressing reminders

Distressing reminders evoke memories of a traumatic event, and cause negative, aversive feelings, but our front brain remains mostly online. They occur within conscious thought (we know why we’re triggered) but there may be some unconscious elements to them as well: we can describe them, but not always explain them. It is a reaction partly in our body, and partly in our brain; partly in our front brain, and partly in our back brain. Technically, the process is mediated both by our amygdala (our smoke alarm) and our hippocampus (our context stamp). As we’ll see, the key to dealing with them is via soothing, specifically activating our front right brain, the right orbitofrontal cortex, and we can learn to deal with them while they’re happening.

Uncomfortable associations

Uncomfortable associations are links we have made in our mind with our trauma. They occur consciously and we can explain verbally what is going on for us, for example: ‘I don’t like pictures of trees, because they remind me of where the abuse took place.’ It’s a reaction that occurs within our brains rather than bodies; our front brain is still engaged and online; and the process is mediated by the hippocampus as it draws on explicit memory. We deal with these associations through reframing, specifically via our front left brain or the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, and we can work on this subset of triggers even before they occur.

True trigger |

Distressing reminder |

Uncomfortable association |

|

How it occurs |

Before conscious thought in 7 milliseconds – ‘wordless terror’ |

Within conscious thought, although may have some unconscious elements to it too – we can describe it, although not always explain it |

Occurs consciously and we can explain it verbally |

Body or brain? |

Body |

Part body / part brain |

Brain |

Front or back brain? |

Back brain |

Part back brain / part front brain |

Front brain |

Mediated by |

Amygdala |

Part amygdala / part hippocampus |

Hippocampus |

How to handle |

Noticing |

Soothing |

Reframing |

Area of front brain to engage |

Front middle brain |

Front right brain |

Front left brain |

When to handle |

Afterwards |

During |

Before |

Managing triggers

So if we break down the super-category of ‘trigger’ into these three sub-categories, it can help to make them less overwhelming, and we can figure out different strategies for the three types, based on three parts of our front brain. And we can also prioritise our efforts as we see which types of trigger can be worked on even before we’re triggered; which we learn to manage as they happen; and which we can look at and begin to deal with after they’ve happened.

Managing uncomfortable associations

Let’s start with associations first, as the easiest type to deal with. We may have been abused as a child in a wood, and so we associate trees with abuse. We therefore see a picture of trees in our therapist’s office, and our nose curls up in disgust. There’s a sense that this isn’t right – this isn’t good. ‘Could you take that picture down?’ we might ask. ‘It’s triggering us,’ we explain. We feel uncomfortable, and it would be so much easier for us if we didn’t have to feel that discomfort. The problem with this approach is that there are a lot of trees in the world, and there are a lot of pictures of trees in the world. We can’t remove them all. And this is actually the best level to start at, as it can help us to build confidence in our ability to manage the greater levels of trigger.

The problem here is to with our thoughts. We have made a negative association between the trauma and something that would otherwise be neutral, maybe even positive. So the key here is to engage the front left brain, which is based around words, facts and knowledge. We need to reframe.

So we can start to unpick the associations we have made and replace them with new ones:

Oh look! I am making an association between this picture of a tree and my abuse. I was abused near trees, and so that’s why I’ve made this association. But it’s not a helpful one, because it’s not actually doing anything to keep me safe.

The truth is that trees aren’t dangerous; abusers are. It wasn’t the location that was dangerous; it was the person. And this isn’t even a tree; it’s just a picture of one. So, it is an association I’ve made, but I’m going to break that association and I’m going to create a new one instead.

I’m going to imagine beautiful fruit trees in an orchard. I’m sitting under the tree and everything is peaceful and safe. I pick the fruit from the trees – apples, pears, plums – and it all taste delicious. The branches and leaves shade me from the hot sun. It’s nice sitting here by the trees. Trees are lovely. Trees are safe.

It can be helpful to create your own ‘frame’ for your previous trigger and write it down, and then repeat it to yourself several times daily until – as in my example – every time you think of trees, you think of the orchard. That way I can remind myself that every time I see a tree, or a picture of a tree, I can direct myself towards the positive rather than allowing my mind to chase after the negative. It might take a lot of repetition, but it is highly effective in the long run.

If we don’t do this, our life narrows and everything becomes a source of misery. If we want to be free from the effects of trauma, we have to start to learn to take control of the thoughts in our head. It’s not that we can necessarily stop the thoughts coming; but when they do, we can choose to ‘flip’ them from something negative to something positive. Learning that we can start to direct some of our thoughts – guiding them from negative to positive – is a fundamental step in recovery: instead of being powerless victims of our thoughts, we can learn to take charge of them.

Worse still, if every time we see a tree, or a picture of a tree, we replay the negative association, it will grow and strengthen in our mind. And it allows the trauma to infect all the good things in life. Certainly for me, I had to learn to impose a boundary on the trauma – to be able to say, at times, ‘No, you’re not ruining THAT for me as well!’ It takes time, with lots of repetition and perseverance, to change the associations, but if we keep on keeping on, it can massively improve the quality of our life.

Managing distressing reminders

Distressing reminders are more powerful than associations, but not as powerful as triggers. There is an emotional reaction, rather than just a mental one, but it’s not at the level of a full somatic response. It’s upsetting, but it’s still at the edges of my window of tolerance. My front brain is still online a little and so there is some conscious choice over what happens next. The key to distressing reminders is soothing.

Soothing is about letting both our body and our brain know that we’re safe and that nothing bad is going to happen now, so that we can go back into the ‘green zone’ of our window of tolerance. The distress we’re feeling is in our body so it’s important that we address this, not just cognitively, but somatically too. Breathing is absolutely key. It might sound simplistic – of course we need to breathe! – but breathing is a secret super-weapon in our fight against trauma. Breathing sits on the interface between what is conscious and unconscious: after all, you breathe all the time, even when you’re not conscious of doing so, and yet you can also consciously take control of your breathing and speed it up or slow it down.

When we breathe in, it activates our sympathetic nervous system, the amber of fight and flight – our accelerator. So even just one in-breath can make our heart beat slightly faster. Breathing out, however, activates the parasympathetic sympathetic nervous system of the ‘green zone’ – our brakes. So when we’re activated in our bodies by a distressing reminder of trauma, we can override our body’s automatic response by consciously slowing our breathing. It can be useful to breathe in to the count of five, and then breathe out deeply, to the count of five or even longer. For full effect, we can do this mindfully, with our attention on the breath, for a minute or even longer. It’s the most effective response to being triggered, and our breath is available to us everywhere, no matter what we’re doing.

There are other ways to soothe our body’s alarm response too. Many of us trauma survivors find it difficult to actively relax our bodies, and this is because the amygdala is telling us that there’s a fire, so why would we want to relax? Relaxation and fire don’t mix! But when we do relax our bodies, it sends an overriding message to the smoke alarm to say, ‘This is okay! I’ve got this! I’m not concerned!’ The smoke alarm is a two-way device: it sounds the alarm, but we can also tell it to mute the alarm, and we do this by actively relaxing our bodies. How? One of the easiest ways is actually to tense the body. Pick a muscle group – say your quadriceps (front of the upper leg) – and clench them really really tight for as long as you can, say 5 or 10 seconds. Then just let them go. This automatically relaxes the muscles and is far easier than trying to figure out how to make a muscle go floppy which is rigid and tense and ready for action!

The front right brain has the best connections to our body, and is calmed when we calm our bodies. It’s also the part of the brain that is most active in ‘attachment moments’, times when we reach out to a significant person, another human being who is attuned to us and can provide a safe haven for us when we’re distressed. It’s not always appropriate or possible to get help from people – people aren’t always available – but sometimes they are and just a little cry for help at these moments can help pull us back into our green zone. Who can you reach out to? And even if they’re not available, can you imagine a conversation with them in which they are telling you that you’re okay?

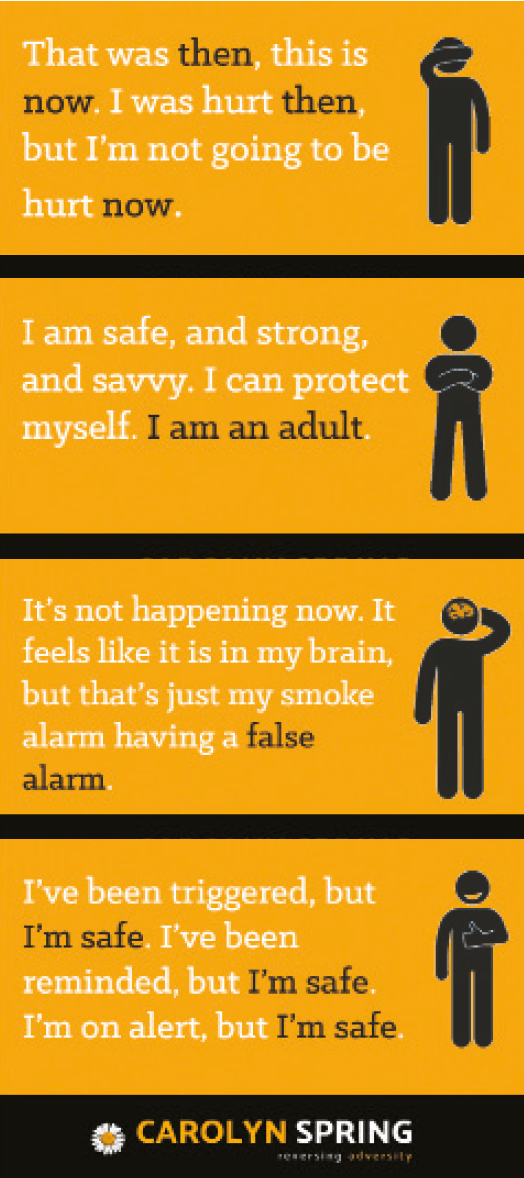

In addition, we can send mental messages to our smoke alarm to calm down, with reassuring mantras. For example:

It’s okay. It’s just my smoke alarm sounding. But it’s a false alarm – just burnt toast, not the house on fire. I’m safe now. My body and brain have noticed something that reminds them of the trauma, and they’re trying to protect me. But that danger was then; this is now, and I’m safe. No need for the smoke alarm. I can breathe, and relax.

Managing true triggers

If we can become proficient at reframing our uncomfortable associations, and soothing our distressing reminders, then we can move on to tackling the most difficult level of trigger, the ‘true trigger’. This is the full-blown, all-out emergency that can at first be almost impossible to deal with. We go either into the amber zone, with fight or flight, manifesting even in a panic attack, or we tip even further into the red zone and we shut down with freeze. How on earth can we manage when this is happening?

To start with, we can’t. We can only work on ‘repairing’ the brain after the event. It is very common, after being triggered like this, to feel shame and frustration. ‘What happened? Oh no! I can’t believe I was triggered again!’ We unleash a verbal torrent of abuse on ourselves for having reacted the way we did, or we feel helpless and overwhelmed at our inability to prevent it. Either way, our attack on ourselves sends a new message to the amygdala that we are under attack. It can’t distinguish between a real attack from an outside source, and an internal attack from ourselves: it just sounds the alarm! So we end up in a vicious cycle: we get triggered, and then afterwards we attack ourselves for having been triggered, which triggers us further.

So we may not be able – at least to start with – to stop the initial trigger, but we can do something afterwards. We can be kind to ourselves, and we can just notice the fact that we were triggered, without judgment or criticism. We can say, ‘Aah! I was triggered! How interesting!’ If we can take all the blame out of it, it will at the very least prevent us from being triggered again. It’s like stubbing our toe and then whacking ourselves on the head for being clumsy – we end up not just with one pain, but two!

Self-compassion turns down the sensitivity of the smoke alarm. Staying calm after the event gets the smoke alarm to see a trigger as just ‘one of those things’, but not as representing real danger. Because afterwards, nothing bad happens. I’m walking through the woods, a dog runs up to me, I get triggered … and I may even lose time as I switch to a traumatised part of myself. But afterwards, as my front brain comes back online, I can look back at what happened and I can say, ‘I was just triggered – that’s all it was. Nothing bad happened. I’m safe.’

I like the word ‘just’. It helps defuse situations. It gives a shrug of the shoulders to something that otherwise is clamouring to shout ‘DANGER!’ It’s an important part of overcoming trauma. Because all of these reminders of trauma feel like they’re an emergency; it feels like we’re going to die. And we can validate these feelings, because yes – we really do feel this. But we mustn’t believe them, because it’s okay now and we’re safe.

If we keep telling ourselves we’re unsafe, we’ll keep on being triggered. The key to recovery from triggers and flashbacks is to work towards feeling safe. And so we have to start telling ourselves that we’re safe even before we feel we are. We have to base what we tell ourselves on external reality, rather than internal feelings. Are we actually safe? Even if we don’t feel it, we need to be saying it, and the word ‘just’ can help us to tune things down a little. ‘I’m just triggered … It’s just a tree … It’s just a dog … It’s just my smoke alarm sounding … It’s just trying to keep me safe.’

REFRAMING EXAMPLES

-

‘Oh look – I’m thinking that thought again that it’s dangerous to stay in a hotel room. That’s my brain trying to keep me safe because bad things happened previously in hotel rooms … So let’s weigh this up. Are hotel rooms intrinsically dangerous? What about this particular hotel room? How can I check out if it’s safe or not? How can I acknowledge that my back brain is trying to keep me safe, whilst allowing my front brain to make a fresh risk assessment based on the real here-and-now?’

-

‘Oh look – I’m thinking that thought again that I can’t trust men. This is because I was abused by some men. But it wasn’t the fact that they were male that caused my abuse. It was their choices as individuals. There are many men, even ones that I know now, who haven’t abused me. So how can I acknowledge that my back brain is trying to keep me safe, whilst also getting my front brain to perform a risk assessment based on these unique, individual men that I’m going into this meeting with?’

-

‘Oh look – I’m thinking that thought again that the word ‘abuse’ is triggering. That’s my brain trying to help me avoid remembering the abuse that I suffered, and it helped me survive psychologically when I was a child. But right here, right now, it’s just a word made up of five letters. It refers to all sorts of things – it’s not specific to my abuse. It might be that I can learn something that will help me with my recovery, and I don’t want my life to be narrowed by trying to avoid it all the time. It’s just a word. It can’t hurt me.’

So to manage true triggers better, our first step is to ‘just notice’ that they’ve happened, and be compassionate and reassure ourselves that we’re safe now. We learn to calm down quickly after having been triggered, so that at the very least we are minimising the harm.

The next step is to build reassuring mantras into our everyday thinking, to train the conscious mind so that our unconscious mind can start to do things habitually. These are the kinds of mantras I mentioned above for ‘distressing reminders’. It’s utilising the same concept as training for paramedics or people in the military – people who absolutely have to stay calm even in the midst of a crisis or a full-blown attack. They are drilled, over and over again, to keep their front brains online even while bullets are flying overhead, or a patient is in cardiac arrest. And many of them have simple mantras: ‘ABC: airways, breathing, circulation.’ Rather than freaking out and not knowing what to do, the emergency responder can fall back on doing the basics: the ABC. In the military, the most basic is ‘ready, aim, fire!’ You don’t want someone to fire a gun until they’ve readied themselves in position and taken aim. You train the conscious mind so that it becomes a habit even under difficult conditions. And that’s the same process that we can use to learn to manage triggers.

Making your own mantras, which make most sense to you, is most effective. They must be short and simple – able to be repeated easily, maybe using rhyme or alliteration to plug them into memory. Write them down, so that you can keep practising them at all times of day or night, and carry them around as ‘mantra cards’ so that when you are triggered and your front brain is going offline, you don’t have to remember them – you just have to remember where they are. It can also be helpful to let professionals and significant others know about them, so that they can use them if you are too triggered to be able to use them for yourself.

We can recover!

When daily life is consumed with a battle with triggers, it can feel that nothing will ever change and that triggers are impossible to manage. But if we narrow down the problem – if we take the general and make it specific – then we can split the problem up into three types of trigger, and work out a strategy for each. We need to stop and ask: is this an association, a reminder, or a trigger?

- If it’s an uncomfortable association, what can I replace the negative association with? How can I reframe it?

- If it’s a distressing reminder, how can I soothe my body, get support and calm myself down?

- If it’s a true trigger, can I just notice and be compassionate towards myself? Can I practice some mantras that remind me that I’m safe?

The bad news is that this process is hard work and requires dedication and lots of repetition. Our brains are plastic and do change – but not in response to a one-off. If you want to learn a musical instrument, a foreign language or how to drive a car, you have to practice and practice and then practice some more. The same is true for changing the way our brains respond to trauma cues. We can change them, but we need to work hard at it. The rewards, however, are truly phenomenal. I cannot begin to describe how different my life is now from when I was beset with hourly, daily triggers. I’m so glad that I put the time and effort into retraining my brain, and I’m so grateful that I had the support to do it. And I hope you do too.

7 Comments

Carolyn, your offering of actual useful specific advice here has aleady helped me through an association in the last 10 mins. I really relate to your explaination of external triggers and internal triggers chasing each other around a hoop. When I’m full blown triggered into a monster, I then verbally and physically beat myself up for becoming so enraged, and the internal trigger of resembling a care giver from my past. I will keep trying to notice this and be compassionate to myself – however hard that is when shame shrouds me on all its levels.

I also find mentalising really helpful when my brain wants to reach out but I have no care givers that I can turn to, or other people who understand the subtleness of dissociation and might mirror useful soothing or helpful human connection techniques.

You inspire me by the work you are doing to help educate the ‘world’ what actually happens to our development through trauma and dissociation at the most extreme end of the spectrum.

Is it possible to have this as a Pdf or easy print as it would be wonderful to share this incredibly insightful article with my clients? thanks

Carolyn, Nobody, literally nobody, gives such incredible advice and help like you do. Through your own experiences you have turned that into such a positive thing by helping thousands of people to understand how to recover from such deep trauma. May your work continue for many many years. Thank you doesn’t cover my appreciation for all that you have taught me. You are truly an inspiration. I have read many books and I have never had anything like the information that I get from you.

Thank you for such kind words, Jill! Much appreciated.

Thanks for the advice and information. I am reminded of a helpful guided meditation by Jim Kitzmiller on YouTube that used the phrase ‘observe ourselves’ I think for me it helped engage my middle brain in a similar way to your use of the term ‘notice’ . I like learning about why the techniques work, it helps me remember them and customise them.

I discovered your work 3years ago. I get so much from your articles and you have given me tools to deal with triggers and dissociation. I have recently started working with a trauma therapist and will be lending him your book which I am having for Christmas. Thank you so much.

Thank you for an extremely helpful article! It’s good to know that there are techniques and mantras to help to live a happier life and to control the triggers. I am really grateful to your sharing of such insightful information. Thanks again!